Art Fauvism is an art movement that exploded onto the French art scene around 1905. It was the first true avant-garde movement of the 20th century.

While it was incredibly short-lived (lasting only about three or four years), it was revolutionary because it liberated color from its descriptive role. For the first time, artists argued that a tree didn’t have to be green and the sky didn’t have to be blue. Color could be used purely to express emotion.

Here is a detailed breakdown of the movement.

1. The Origin: “The Wild Beasts”

The name “Fauvism” began as an insult.

The Event: In 1905, a group of young painters (led by Henri Matisse) exhibited their work at the Salon d’Automne in Paris.

The Shock: The public was horrified. The paintings looked like they were painted by children or madmen—loud, clashing colors and rough brushstrokes.

The Critic: Art critic Louis Vauxcelles saw the chaotic paintings surrounding a classical, Renaissance-style statue in the center of the room. He pointed to the statue and joked: “Donatello chez les fauves” (“Donatello among the wild beasts”).

The Result: The name stuck. The artists embraced it. They were the “Wild Beasts” of art.

2. Core Philosophy & Characteristics

Fauvism was not about a strict theory (like Cubism); it was about a shared desire for expression.

Arbitrary Color: This is the golden rule. Color was chosen for its emotional impact, not scientific reality. If the artist felt the scene was “hot,” they might paint the ground red.

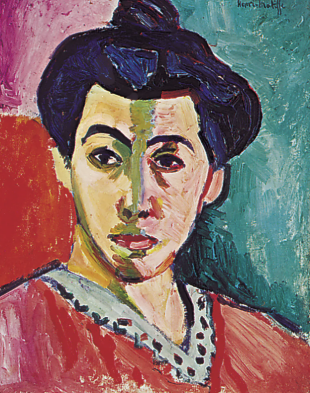

Example: In Matisse’s The Green Line, he painted a green stripe down the center of his wife’s face to depict light and shadow.

Paint Application: They applied paint directly from the tube, often in thick, unmixed smears or dashes. They didn’t care about smooth blending.

Simplification: They rejected the 3D shading of traditional art. Figures and landscapes were flattened into simple shapes outlined in heavy colors.

Hedonism: Unlike German Expressionism (which used distortion to show anxiety and horror), Fauvism was generally optimistic, joyful, and decorative. Matisse famously said he wanted his art to be “like a good armchair”—a rest from physical fatigue.

3. The Key Artists (The Trio)

While many dabbled in the style, three men defined it.

A. Henri Matisse (The Leader)

The oldest and most intellectual of the group. He was the “King of the Fauves.”

Style: Calculated and balanced. Even when using wild colors, his compositions were peaceful.

Quote: “Expression, for me, does not reside in passions glowing in a human face… The whole arrangement of my picture is expressive.”

Famous Work: The Joy of Life (Bonheur de Vivre) — A golden, idyllic landscape filled with nude figures, painted in bright orange, yellow, and green.

B. André Derain (The Bridge)

He worked closely with Matisse and often acted as the middle-ground between the classicists and the wilder painters.

Style: He is famous for painting London. Unlike Monet (who painted London in fog), Derain painted the Thames river in bright yellows and blues.

Famous Work: Charing Cross Bridge.

C. Maurice de Vlaminck (The Rebel)

A proud, self-taught painter who was also a musician and cyclist. He was the most aggressive of the group.

Style: He used paint like dynamite. He hated the “rules” of art school and wanted to burn them down with his colors. He often squeezed paint tubes directly onto the canvas.

Famous Work: The River Seine at Chatou.

4. Influences

Fauvism stood on the shoulders of the Post-Impressionists who came just before them:

1. Van Gogh: From him, they learned that color equals emotion.

2. Paul Gauguin: From him, they learned to use flat fields of color (Primitivism).

3. Seurat (Pointillism): Matisse and Derain took the tiny “dots” of Pointillism and exploded them into large “dashes” of color.

5. Notable Works Table

Artist Title Description Why it matters

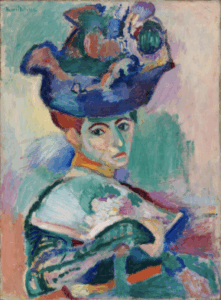

Henri Matisse Woman with a Hat (1905) A portrait of his wife wearing a hat, painted with green, yellow, and purple patches on her face. The painting that caused the “Wild Beast” scandal. It proved a portrait didn’t need realistic skin tones.

Henri Matisse The Dance (II) (1910) Five red figures dancing in a circle against a blue sky and green earth. The ultimate simplification. Only three colors are used to create intense energy.

André Derain Mountains at Collioure A landscape where the mountains are orange/red and the trees are blue. Shows the complete rejection of atmospheric perspective.

Maurice de Vlaminck Restaurant de la Machine A suburban scene painted with violent, swirling thick paint. Shows the influence of Van Gogh’s heavy texture.

6. The End of Fauvism

Fauvism burned bright and fast. By 1908, it was effectively over. Why?

It was a transition, not a destination. The artists felt they had done everything they could with pure color.

The Rise of Cubism: Picasso and Braque arrived on the scene with Cubism (which focused on shape and removed color). This became the new avant-garde trend.

Irony: Georges Braque was actually a Fauvist for a brief moment before he invented Cubism!

Diverging Paths: Matisse continued to explore color for the rest of his life, while Derain and Vlaminck returned to more traditional, darker styles of painting.

Route

Art Galerie Marketplace

Secondary phone: +55 31 99506-1099

Email: service@artgalerie.com.br

URL: https://artgalerie.com.br/

| Monday | Open 24 hours |

| Tuesday | Open 24 hours |

| Wednesday | Open 24 hours |

| Thursday | Open 24 hours Open now |

| Friday | Open 24 hours |

| Saturday | Open 24 hours |

| Sunday | Open 24 hours |