Conceptual Art is a movement where the idea (or concept) behind the work is more important than the finished art object. In fact, in many cases, there may be no physical object at all—only a set of instructions, a photograph documenting an action, or text on a wall.

Emerging in the mid-1960s and 1970s, it was a radical challenge to the definition of art. Conceptual artists argued that art is not about technical skill or aesthetics (beauty), but about meaning and language.

Here is a detailed breakdown of the movement.

1. The Core Philosophy: “Art as Idea”

For centuries, art was judged by the quality of the object (e.g., “Is this painting beautiful?” or “Is this statue realistic?”). Conceptual artists rejected this entirely.

Dematerialization: They sought to “dematerialize” art—to remove the physical object so that it couldn’t be bought, sold, or treated as a luxury commodity.

Anti-Aesthetic: They didn’t care if the work was “boring” or “ugly” to look at. The visual aspect was perfunctory; it was just a vehicle to communicate an intellectual idea.

The Artist as Planner: Sol LeWitt, a pioneer of the movement, famously said: “In conceptual art the idea or concept is the most important aspect of the work… all of the planning and decisions are made beforehand and the execution is a perfunctory affair.”

2. Historical Context

Conceptual Art didn’t appear in a vacuum. It was a reaction against Modernism and Minimalism.

Marcel Duchamp (The Grandfather): In 1917, Duchamp presented a urinal signed “R. Mutt” as art (Fountain). This “Readymade” proved that art is defined by the artist’s intent, not their craft. Conceptual artists worshiped Duchamp for this.

The 1960s Political Climate: In an era of Vietnam War protests, feminism, and civil rights, artists felt that making pretty paintings for rich collectors was irrelevant. They wanted art to be an intellectual tool to question authority and institutions.

3. Key Characteristics & Methods

Since there is no single “style,” Conceptual Art is defined by its methods:

Language/Text: Using words instead of images. If the idea is the art, why paint a picture of it when you can just write it down?

Documentation: Using blurry photos, maps, graphs, or videos to prove an event happened. The photo isn’t the art; it’s just evidence of the art.

Instructions: The artist provides a set of rules, and anyone can “make” the art. This destroys the idea that the artist’s “touch” is sacred.

4. Key Artists & Famous Works

Artist Key Work Description Why it matters

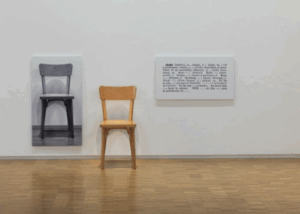

Joseph Kosuth One and Three Chairs (1965) An installation with a real chair, a photo of that chair, and a dictionary definition of the word “chair.” It forces you to ask: Which is the real chair? The object, the image, or the idea (language)?

Sol LeWitt Wall Drawings LeWitt wrote instructions (e.g., “Draw a red line 10 inches long”). Other people executed the drawings on gallery walls. It proved the artist doesn’t need to touch the artwork for it to be theirs.

John Baldessari I Will Not Make Any More Boring Art (1971) He punished himself by writing this sentence over and over like a school child, or having students do it. An ironic critique of art schools and the “boring” nature of Conceptual Art itself.

Piero Manzoni Artist’s Shit (1961) He canned his own feces in 90 tin cans and priced them by weight based on the current price of gold. A savage satire of the art market—collectors will buy anything if a famous artist signs it.

Yoko Ono Grapefruit (1964) A book of instructions, such as “Listen to the sound of the earth turning.” Shows how art can be purely imaginary and exist only in the viewer’s mind.

5. Institutional Critique

A major sub-genre of Conceptual Art was Institutional Critique. Artists used their work to attack the museums and galleries that displayed them.

Hans Haacke famously researched the shady real estate dealings of a museum trustee and displayed the incriminating photos and documents inside the museum (which led to his show being cancelled).

This proved that art could be a form of investigative journalism and political activism.

6. Why is it so controversial?

Conceptual Art is often the hardest style for the general public to accept. You often hear: “I could have done that!” or “Is this a joke?”

The Response: The Conceptual artist would reply, “You could have done it, but you didn’t.” The value isn’t in the doing, it’s in the thinking of it first.

The Legacy: While “pure” Conceptual Art faded in the late 70s, it permanently broke the rules. Today, almost all contemporary art is “conceptual” in some way—installation art, performance art, and digital art all rely on the freedom won by this movement.

Route

Art Galerie Marketplace

Secondary phone: +55 31 99506-1099

Email: service@artgalerie.com.br

URL: https://artgalerie.com.br/

| Monday | Open 24 hours |

| Tuesday | Open 24 hours |

| Wednesday | Open 24 hours |

| Thursday | Open 24 hours |

| Friday | Open 24 hours |

| Saturday | Open 24 hours |

| Sunday | Open 24 hours Open now |